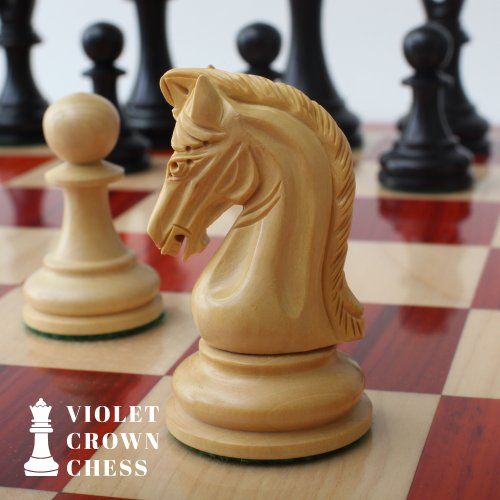

English Ornamental "Barleycorn" Ivory Chess Set, mid-19th century

Mid-19th century English ivory chess set with Barleycorn pattern, which apparently was turned with an ornamental lathe. One side natural, the other side stained red. The Kings have beautiful crowns with a cross pattée finial, the Queens with a feather finial. King size is 10.8 cm (4.35"). The rooks as small turrets on a pedestal and with large flags on top. The fine carving of the knights reminds of the style of the workshop of George Merrifield. The bishops with deep mitre cuts. The pawns with ball finials on baluster stems. All pieces on ornamented circular bases.

It seems that the maker of these fantastic chessmen tried to demonstrate the potential of his ornamental lathe to the fullest. Ornamental turning goes back to the Renaissance, but mechanical ornamental lathes as the one most likely used for this chess set were developed in the late 18th century. Among the most famous makers of such lathes was John Jacob Holtzapffel (1768-1835), an Alsatian mechanic, who moved from Strasbourg to London in 1784. Ten years later, he set up his lathe-making business, which was first operated from premises in 118 Long Acre (1794-1811) before moving to 10 Cockspur Street (1812 to 1820) and to 64 Charing Cross (1821 to 1901). From 1795 to 1803, he produced and sold 385 lathes, including his first rose engine lathe in 1797. John's son, Charles Holtzapffel (1806–1847), joined the firm in 1827 and continued to run the business after his father's death. He set about writing a treatise published in several volumes entitled "Turning and Mechanical Manipulation", eventually running to some 2,750 pages. Volume 1, "Materials, Their Differences, Choice, and Preparation; Various Modes of Working Them, Generally Without Cutting Tools," was published in 1843. Volume 2, "The Principles of Construction, Action and Application of Cutting Tools Used by Hand; And Also of Machines Derived from the Hand Tools," was published in 1846. Vol. 3, "Abrasives and Miscellaneous Processes, which Cannot be Accomplished with Cutting Tools," remained uncompleted when Charles died at age 41. It was published after his death by his son, John Jacob Holtzapffel (1836–1897), who completed Vol. 4, "The Principles and Practice of Hand or Simple Turning," which was published in 1879 (he also made the 750 woodcut illustrations that it contains) and Vol. 5, "The Principles and Practice of Ornamental or Complex Turning," which was published in 1884, both of which are today also referred to as the "bible" of ornamental turning.

The Holtzapffel family was not the only famous maker of ornamental lathes. Other well known makers were John Evans (1787–1858), originally from Wales, who is said to have worked for the Holtzapffel firm before starting his own ornamental turning manufacturing company in 1810, for which he advertised as "Engine, Lathe & Tool Manufacturer and General Machinist." and in particular his grandson John Henry II (1843-1919), who took over the business in 1874 shortly before his father William died. He was a prolific writer, having contributed more than 300 articles to the "English Mechanic & World of Science" magazine from 1881 to 1916 as well as several articles for the "Forge and Lathe" and the "Journal of the London Amateur Mechanical Society". His major work was a book simply titled "Ornamental Turning" which covered the subject in complete detail (second only to Holtzapffel's Volume V). Apart from the aforementioned, several other manufacturers have to be named for their contribution to the development and improvement of ornamental lathes, such as William Hartley (1821-1886), who developed a compound geometric chuck around 1845, which combined several "sun and planetary motions", thus creating a completely new way of giving motion to the chuck, William Goyen (1814-1898), George Birch (1842-1900) and James Lukin (1827-1917).